Peggy Turnbull

The Pilgrimage Home

After midnight in Milwaukee, I trudged up and down the gray stairwell of a parking ramp, as if lost in an M.C. Escher lithograph, unable to find my car, while aural memories of the Leonard Cohen concert resonated in my brain. At last two kind strangers helped me to decipher the non-sequential numbering of the garage’s floors and stalls. And there it was, the aging silver sedan that was my steed for the trek ahead.

In the city, snow fell in elongated drips and slid off my windshield. By the time I passed the last suburb, a March storm pelted ice crystals onto the slick road. Conditions crumbled as I continued north. The rear-view mirror revealed a line of drivers behind me, following in my wake. As a timid driver in foul weather, I was appalled to be in front, but I shepherded them safely through the snow until the moment all distinctions among median, road, and berm dissolved. The world was an unending series of wind-blown drifts. My tires slipped and I faltered, disoriented. I reduced my speed to a crawl. A semi lumbered past and pulled ahead. Hallelujah. I followed its two tiny red stars through the blustery night as it sped forward. After they faded, I traced the truckers tracks onward, though the mess from the sky was quickly filling in their indentations.

And yet this moment was my salvation. It brought me to an epiphany. This was a pilgrimage, not simply a journey home. I had spent hours in the presence of a man who regularly spoke with God. He sang, humbly, on his knees often, and honored his fellow musicians by doffing his fedora, holding it to his heart, and bowing reverently during their solos. Cohen’s music wove sacred scripture and Jewish prayers into popular songs. Joni Mitchell called him a holy man. And so, at some time in the evening, a channel opened between me and the divine. It didn’t make me feel safe. It simply meant that whatever happened on the interstate highway was significant in an other-worldly way.

As the blizzard’s white lines slanted toward me, a segment from Who by Fire played repeatedly in my mind. The song was inspired by Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. What captivated me was not its litany of death but the silence after Javier Mas’s bandurria solo, followed by a note so profound I felt it in my belly as if it were my long-absent beloved.

One by one the strangers behind me slipped away to cities and farms and left me alone on the howling road. Though I tried to focus on memories of the concert, sleep slithered in to wrestle me. I opened the window and greeted the gush of frigid air as a friend, but it was a cold and prickly companion. So I drowned out the beauty of my private mental concert with radio noise.

As I navigated the dangerous highway, I wondered what the storm was saying. The angry weather seemed designed to stop me, to interfere with my homecoming, as if the gods were chasing me to retrieve something I had stolen from them, something humans are not allowed to have.

In Sheboygan County, the northerly wind became westerly. Snow skittered across the interstate and fierce blasts buffeted the side of the car, almost shoving me sideways onto the berm. The gusts blew the road clear in spots and I kept my bearings. The likelihood of my death by accident began to fade.

In Manitowoc County, the road was covered in ice. But I joined a convoy of cars under the protection of two tractor-trailers. The early morning haulers formed a sturdy barricade that eased the last miles of my passage. I whispered prayers of gratitude to whoever was listening. The terror was over.

In my city, there were no signs of the fierce onslaughts I had escaped. The road was a down quilt, clean and thick. I wanted to floor the accelerator in a wild celebratory dance but a cop was stopped near the bridge. I had survived. Joy surged within me like a hymn. The angry gods who chased me over miles of midwestern farmland now knew my mettle.

I owed the universe for my safe travel, for the series of unexpected miracles that were, in reality, ordinary events that came precisely when I needed them. Afterwards, the channel to the divine stayed open. It granted me the strength to write poetry. I had struggled with writing for decades. This time I persevered in the face of doubts and resistance, my commitment to creativity more powerful than before. Poems and other writing are my gifts back to the universe, which I offer with humility. I bow with reverence to the forces that engaged me that night in the same way that Leonard Cohen bowed to his partners in music. May you who read this arrive safely home from your own pilgrimage. May you find the strength you need to travel dangerous paths.

Author’s Statement on Beauty

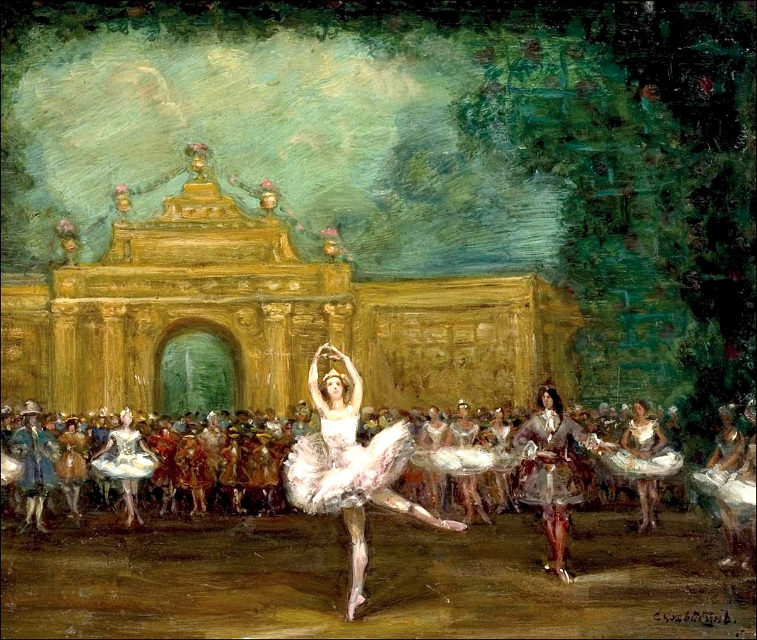

Beauty is a verb. Beauty is a force that tears away the veil between my world and the world that exists beyond the human scale. Beauty extends back into prehistory, encompasses our planet, communicates with us from light years past, lives on into the future. It’s the long line of a wave flowing inexorably to the shore in an infinite cycle. It’s the curving ridges of the Appalachians, ancient and still alive. I am insignificant in the face of beauty. Beauty is bigger than I am. I wept when I heard Brahms’ Requiem. Beauty pierced me, tears flowed. My stomach dropped when I watched the Joffrey Ballet. The empty space was filled with awe. We think our responses to beauty are personal, individual, but they are not. The shared experience of beauty links us to other humans. Three people in separate neighborhoods watch the snow fall from their windows. One writes a poem about a lace curtain that moves. Another calls her daughter, remembering the time they walked together in a similar snowfall. The third takes to his bed, lovesick for a woman he can’t have, the snow’s quiet beauty intensifying his loneliness. Beauty is a spirit that moves among us. As human beings, we may not agree on much, but there are moments when we can agree on beauty. Beauty has the power to unite us.

Peggy Turnbull is inspired by the landscape and seasons in her home state, Wisconsin, U.S.A. She worked as an academic librarian for many years until retiring to become a poet. Her poems have appeared in Rat’s Ass Review Love & Ensuing Madness Collection, Post Heroin Chic, Communicator’s League, and forthcoming in Muddy River Poetry Review. One of her favorite sounds is the call of a Sandhill Crane. More at: peggyturnbull.blogspot.com.