Wally Swist – Five Poems

Beneath So Many Lids

Rose, oh pure contradiction, joy

of being No-one’s sleep, under so

many lids.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell

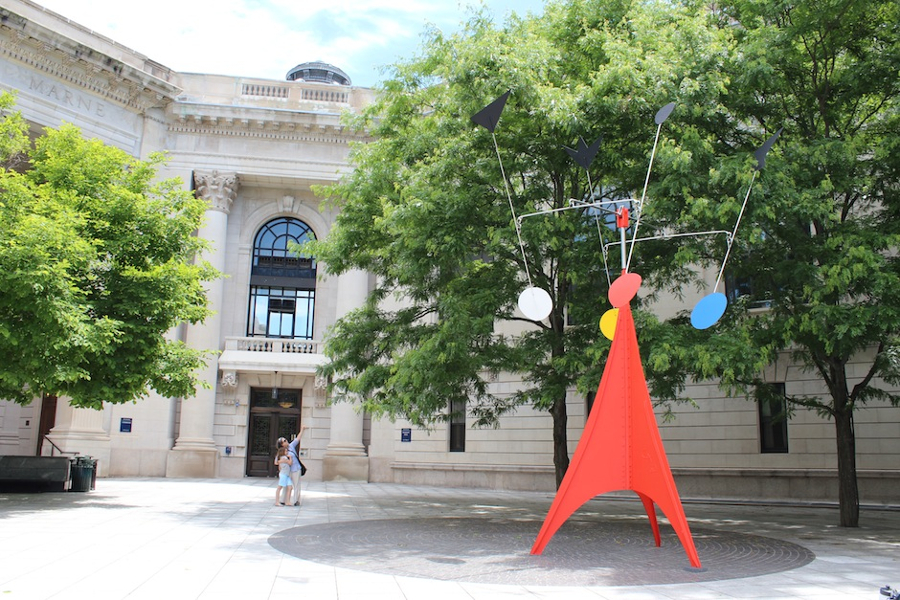

We would meet passing on the street,

often in front of Woolsey Hall, near

Calder’s metal mobile, Gallows and

Lollipops, between classes,

students rushing around us,

you speaking with excitement about

the translations of Rilke

you had begun, me listening

avidly, when you would open that

gold-colored latch of your worn

leather briefcase, and pull out a sheaf

of freshly-inked poetry on white sheets.

You would diligently hold

the pages in the air in one hand while

pointing to lines that held the music

of the meaning you were

trying to bring into our inadequate

English from what you referred to as

being the pure music

of the German. So many years now

since those translations have become

known as the most accomplished

to be rendered into our language.

In those moments, with the throngs

of students flowing around us,

and you passionately gesticulating,

my wide eyes taking in the dark

type that contained

the light of the mystic vision

you hammered into words onto

the page with the keystrokes

of your typewriter, as Calder had

soldered his multicolored geometries

into place to pivot

against each day’s

juxtaposition of changing sky—

there the two of us stood,

our shadows merging

momentarily, beneath the Matisse-

like discs of whimsy

and delight, our imaginations

expanding to what you were realizing

in the pointed discipline

in which you were releasing

the poetry in the written word of Rilke,

of being able to express

what is ineffable; similar to that

rose, Rilke’s epitaph, on his tombstone,

whose contradiction it is

that such a joy is the sleep of

no one person, beneath those many lids.

A Dream like Ours

I must tell you

what your words do—

how they fill me.

May you infuse the distance

between us in such a way.

May what I feel for you

immerse you, always; in this

dream that is ours,

from which, if I ever do

awaken, may it be looking

into your face, whose

depths are inherent with

such intrigue they reveal

themselves with

mystique, so that I am

always surprised, due to

my disbelief, that it is you

who are the one here

with me; it is you

I see as I open my eyes.

La Vie en Rose

I just thought you might like to hear

about my newest recipe, as inspiration:

langostino and mussels marina over

spinach and chive pasta, with sautéed

garlic, scallions, sweet onions,

and shredded carrot. It also contains

some basil and chicken stock.

I steamed the mussels first, and

allowed them marinate in the broth.

Then I cut the langostinos in half,

so I can rationalize buying only a few

ounces of this delicacy, since I freeze

the other half. Additionally, I squeeze

a quarter of a lemon onto each serving.

Now I have enough langostinos for

a second preparation of this dish.

This meal should really be served with

a small salad of arugula and cherry

tomatoes in olive oil and balsamic.

More importantly, the dish should also

be complimented by a glass of French

red wine. I went again with what

I happened to have opened: La Passion

Grenache, 2011, and as the vintners

intimate: it is mouthwatering, the tannins

are ripe; and the fruity blackberry taste

is more pronounced than those hints

of liquorice, all highlighted by a soupcon

of herbs. One glass of this and

you are in heaven; a second glass offers

your being in heaven and not wanting to

leave: ever. If you are fortunate enough

to enjoy this repast, you won’t help

but raise your glass in gratitude after

you have cleaned the contents

of your bowl, to toast how absolutely

extraordinary it is just to savor dinner—

what it is to be alive.

Letter to K.

I am writing you to inform you that I am disengaging.

My disengaging, at this time, could not be more significant.

I am disengaging because it is a continual lesson in futility

for me to keep going to see you, even on Mondays, which

seemed to be our established day to visit. That

you are not there, has deflated me, at least on occasion,

since I often enough have found this to be a lesson in

deepening my own practice of patience. I am disengaging

because I believe in an active spirituality. My old mentor,

would often say that if you spoke too much about your

spiritual development it would deplete it, much like water

going over a dam. You talking about spirituality as much

as you do, in my opinion, does the same thing, especially

when I see that you talk about it often enough but that

you can’t access it. As the modern mystic, Carolyn Myss,

has said, Many people have these books on the shelf but they are not

able to access them. Would it be too much for you to just

email me or call to let me know that you are not going to be

in on a Monday, especially when you tell me that you even

look for me on Mondays, which then leads me to make

time out of my own day to see you on Mondays? Apparently

it is. I am unable to use the chair you brought me because

of the smell of kerosene that emanates from it will ruin

my clothes. However, I am not offering that as a ruse

for you to pick it up. I just wanted you to know that

as kind of a gesture as that was it did not work out for me.

I know you are in ill health. Both of us are at crucial

crossroads: questions to answer; decisions to make;

discovering a true path that will affect us and those

we come into contact with; whether to remain

in the area or to choose another place in which to live

out our lives. I wish you the best: spirit and soul,

body and mind, goodness and truth. There has been

no one who has enhanced my life more than you have

over these many years. No one has inspired me

in my entire life as you have: so much so for the best.

I send you wishes for the same: become well, do fine

things, take the best care of yourself, especially when

you are at your most vulnerable. Saying thank you

to you for the love that we have shared, and it has been

love, will fall far short of being apropos. So, I posit

that we might want to keep moving within the boundless

light of this love for the rest of our lives, which is what

carries us and protects us whether we will it or not.

The Tangible Plane

My answer is yes. Yes, to the your phrase,

your rubric, that you send to me. Yes, what

a spark, and series of sparks. However, it is

now my experience, as it was my intuition,

that relationships of depth between a man

and a woman need nurture; and distance,

space, and time are disruptive physical

modulations in the alchemy of Eros, which,

if we can define that elemental archetype is

the Higgs boson of romance, the incandescent

radiance of the beloved. This is what

fills the poetry of Rumi. It is what the Sufi

dervishes whirl in harmony with, and it is

in their dancing, that their hearts dance,

and it is in this dancing that our own hearts

spin in the dance with each other.

Our technology is incapable of replacing

the magnitude of knees touching over

dinner and wine. iPods are not hardwired

in replicating a feasible alternative for that

irresistible magnetism of two people leaning

over to kiss, and, at least, momentarily,

becoming lost in themselves, amid whatever

din that may surround them, so much so

that they actually create their own brief

island of solitude in the current of time.

Meeting on the tangible plane is still

a possibility for us. And meeting you

in the way that I met you and for us

to have experienced the electricity

in the connection between us was

certainly miraculous. It is hubris

to even think for an instant that

the miraculous can be a way of life;

however, it is when we become

humbled by the power of the miraculous

does it become practice and path.

You are a singular rose of a woman;

may you continue to blossom and bloom.

Yes, may we meet on the tangible plane;

may the vectors of our meeting align;

and may they be provident for us both;

but may we always savor the alembic

of the distilled lavishness of our repose.

Author’s Statement on Beauty

Beauty is relative—however, it is also abundant and perennial. One type of beauty may diminish and morph into a deeper philosophical truth. Beauty can take the guise of morality and define the outer reaches of what it means to be fully human—to grow into that.

The film Amour, directed by Michael Haneke, which was made in 2012 and won the Palme d’Or, is, ostensibly, all about beauty and what is beautiful about life, as well as what are intrinsic elements of living that may be seen as being opposite to beauty. The film’s characters are a husband and a wife, two former music teachers, in their twilight weeks and days. Jean-Louis Trintignant is Georges and Emmanuele Riva is Anne. They are retired. They are cultured. They read, go to concerts, enjoy each other’s conversation, and still love each other—for the most part. Anne once shocks Georges by saying, as wives often enough stun their husbands by their appraisals of their characters, “You are a monster.” However, she clarifies that declarative sentence by adding “But you have been kind.” That is beautiful.

After a lifetime of marriage to each other, Anne suffers two strokes and Georges cares for her throughout her decline. He bathes her, feeds her, exercises the leg on the side she can no longer feel, practices speech therapy with her. Many men, or wives, for that matter, would never have the wherewithal or the courage to brave such lengths—of true amour. Georges may be guilty of being a monster, in Anne’s experience, but he is the precipitant in furthering the spark of beauty between them. The drama may seem very French, something Camus or Sartre would have taken delight in, with both Georges and Anne seeing the end of their lives in plain sight; however, instead of being grim, they rise above the end of life, in uncommon transcendence. In their amour, and its tacit veracity—there are several touching scenes regarding Georges physical care for Anne, which are truly heartrending in their depth of humanity and active loving—the viewer is offered the essence of what love is and what having an affair is not. Hence, the irony in the film’s title. In today’s world where greed, sex, and narcissism are common, the beauty of Georges and Anne is exemplary as not only a moral and cultural pedagogy without pedantry but, quite aesthetically and humanely, one act of beauty after another. Through another’s lens this might be seen as hardship and turmoil, unimaginable spousal duty and death in life.

At the film’s end, without giving anything away, Georges is clipping the flower heads from a bunch of daisies he has just purchased at the florist. He fills the kitchen sink and scissors the flowers into the water, then throws away the stems. These are meant for his Anne. Often we need to practice the art of discernment in order to see clearly. Sometimes we need to ruin the flowered stalk to create a ritual for celebration. As Anne says, in one scene, over dinner with Georges, while looking through photograph albums, “It’s beautiful.” Georges responds, “What?” Anne answers, “Life. So long.”

That is what constitutes perennial beauty and remains beautiful. If we allow ourselves to discover the epiphany in the commonplace in our lives, we realize, to our astonishment, that all along, through every disappointment and affliction, we can say, “it’s beautiful.”

Wally Swist’s books include Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012); The Daodejing: A New Interpretation, with David Breeden and Steven Schroeder (Lamar University Press, 2015); Candling the Eggs (Shanti Arts, LLC, 2017); and Singing for Nothing: Selected Nonfiction as Literary Memoir (The Operating System, 2018). More at: wallyswist.com.