Linda Parsons – Three Poems

The Only Way

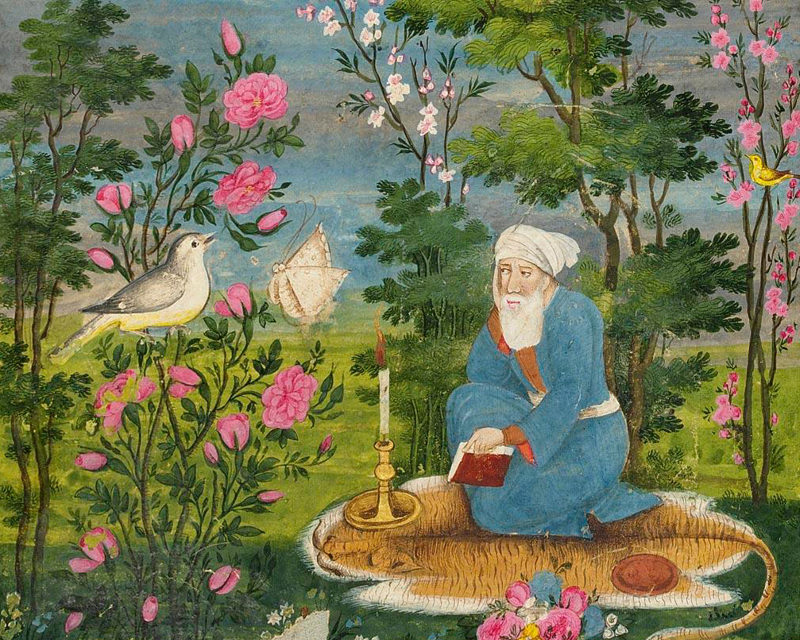

There are a hundred ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

—Rumi

Honor your grief, every whim and chore,

in the checkout lane, the kalamatas he used to buy

too rich for your blood, in the used book shelves,

rank pages he nosed like a dog searching

for its president. However you’ve grieved

in the past is but an anthill to this wail and rent,

a whisker, paltry dust of gone years. Though

grief may deceive in brocade and silks, it thieves

into that rag and bone shop you call heart,

unravels every thread down to hard gristle.

Honor your grief with ragged breath and privation

in the body’s dark cell despite how the blithe world

cries enough. Wait not so patiently for the Full Flower

Moon to shower its blessings, Mars in red opposition.

Turn in place, feather your bare nest, until the only

way is to kiss the ground with pocked knees,

grabble roots like a flathead cat screwed into mud

until finally, sun wrests the scales from your eyes.

The Out Breath Longer Than The In

Take in the acorns popping

underfoot, rippled sandbar of cirrus, the sheepdog’s

nose at hinge of knee, take in the plentiful mast

forecast this winter for the Smokies, that part

of the breath already ragged and blue from predictions

of snowfall closing 441, piggybacked on September

drought, the spell for rain useless as the wedding

gardenias in leathered cellophane.

Take it in, neither drawing

up my height nor bellowing my chest,

but curled under ribs like sage lit at the lintel

I cross, uncertain if I’m coming or going,

the ash of failed days still sweet and blacking

my thumbs.

Now the out breath,

all of its children slapping feet on pavement,

flip-flops on hot tar, summer melons cut

with salt, with mint, with honey. Nightjars’

swoop, the world winnowing to an end

I somehow knew would arrive in gray dawn,

fruit bitten to the sharp core.

Leave a stray refrain,

ebb of my father’s last bed and hours, rubbed

coin of spent marriage. Give it out like alms

to the homeless, tin cup with some rattle left,

some crooked music when the crank

is turned and the monkey clinks cymbals

then slows to dying.

Give it up and out,

the breath no longer yours or mine,

not caught or held or sung but flown.

The Home That Can’t Be Lost,

The Gold That Never Stops Shining

The breath, like the heart,

knows its home: amber light at the lintel,

haint-blue porch, door bleached by high summer.

The breath knows even when I’ve forgotten—

my grandmother’s house on Russell, rooms dreamed

into being, my own veined walls I’ve caulked

and spackled. I’ve waited years to be met

on these steps, to be the fall rose beaming

with last rouge, the topmost figs slick with sweet

despite the near cold, a prodigal unsure

of table or feast.

I’ve prayed for pine ground

under my feet to rebraid the scarred floor,

when the breath could’ve told me to plant

in the muck of unknowing, the mind

a pond, a meadow, the cosmos pebbled

in golddust. Or sit crosslegged in early dark,

a lotus completely at home in the muck,

no longer roaming dogpaths or wilderness,

no longer a motherless child

knocking.

Author’s Statement on Beauty

Linda Parsons is a poet, playwright, and an editor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and the reviews editor for Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel. Her work has appeared in such journals as The Georgia Review, Iowa Review, Prairie Schooner, Southern Poetry Review, Shenandoah and in numerous anthologies. This Shaky Earth is her fourth poetry collection. Parsons’s adaptation, Macbeth Is the New Black, co-written with Jayne Morgan, was produced at Maryville College and Western Carolina University, and her play Under the Esso Moon was read as part of the 2016 Tennessee Stage Company’s New Play Festival and received a staged reading in spring 2017.