Dian Parker

Edward Was Once On a Train

The morning light streams in to bathe Edward in his reverie. In the distance are sounds of morning; rain on the shingled roof, a blue jay arguing with a gray squirrel, the whirr of the refrigerator. He is wearing a tartan wool bathrobe, his bare feet snug in sheepskin slippers. The mug of coffee at his side has long grown cold. He sits very still, an open book on his lap, The Bhagavad-Gita. He can’t imagine how Krishna can sustain the entire world with a fragment of his being when he, Edward Stanwich, can’t even get dressed.

Last night hangs heavy, insistent on resolution.

He’d met Franklin at their favorite pub. They had their usual scotch and made small talk, with much light-hearted jabbing. They talked about Edward’s still not yet completed manuscript. Franklin joked that the earth would pass into its next epoch before Edward was finished and the publishing industry long gone extinct. Why Edward then insisted on telling Franklin his dream was still a mystery. He felt compelled, almost feverish in the telling.

It started like this. “You see, Franklin, I don’t take naps. Never have, too busy and all. Was supposed to be working on my book of Middle Eastern botany. Had this dream. Central Turkey. Egridir, to be exact. Had been there, years ago, but it wasn’t exactly exciting for plants, let alone cacti. Just got smashed on raki with a couple of the villagers and passed out on the bench in the middle of town. Had to be carried to my room. Took the morning bus and was seen off by the whole village. Humiliating.

“Anyway, my dream. I’m in Egridir, walking behind the hills from the hotel. It’s in the middle of the night, very black, no stars, no lights. I climbed up a small rise and suddenly, out of nowhere, was this spot of red. Tiny yet distinct, shimmering in the black like a beacon, glowing. As I made my way towards it, the light grew larger. When I knelt down before it, I instantly saw. It was an HYLOCERUS UNDATAS!”

Franklin waited. Edward waited. They take a sip of drink. Finally Franklin said, “I don’t get it.” At this point Edward knew he should stop. He wanted to stop. The dream was stupid to tell anyone. All dreams were, but he couldn’t stop.

“I tell you, Franklin, it’s like finding an Actaea rubra with white berries. And in Central Turkey? Heavens, it belongs in the tropics! So I dig up the plant with my Swiss army knife, cradling its red berries in my handkerchief. In the distance I hear a train and suddenly, you know how dreams are, I’m in London at the office and get a call. Can’t make out what they’re saying. Switches to Kew, the botanical gardens. I’m leading a tour of other botanists and recognize Carl Linnaeus in the group. The shock wakes me up.”

Edward breathed rapidly. He watched Franklin’s vest rise and fall; slowly, methodically, easily. Edward concentrated on the moving brass buttons but it didn’t help. He kept right on talking. He had to find out, somehow, why he’d had this dream. Maybe then he’d know what to do about his life.

“You see, the point, what I’m saying is this. I have this uncanny feeling that this really happened to me. It’s impossible though – red gylocereus in Central Turkey and then Linnaeus dead for 300 years! Um, what do you think?” Edward’s brow was thick with sweat. Why had he gotten so worked up over a dream? It was humiliating.

Franklin didn’t say anything in the end, only ordered another round of Laphroig and the two men sat in silence, Edward burning with shame.

And so here it is, the next morning, as Edward picks up The Gita to forget last night and forget his dream. Why would he have asked Franklin to interpret his dream? Stupid. Utterly ridiculous.

Edward quickly turns his thoughts to mushrooms, chanterelles in particular. He remembers how his mother collected them in the early morning in the forest at the back of the house and then sautéed them in butter for their breakfast. Only he and his mother and the chanterelles, before school. He recalls the feeling after eating them, as he walked to school along the forest’s edge. Everything seemed brighter, sharper; the moistness in the air, the sunlight sparkling off the birch bark, the sound of the gurgling brook as he walked to school. He would step carefully so as not to disturb the subtle shifts of light and sound. He didn’t want to miss anything, so he moved lightly, like the gait of a deer. He believed it was all caused by the mushrooms, mixed with his mother’s steady love. The golden, wavy tops hidden under dried leaves at the base of a pine tree, with only a hint showing. His mother humming in the kitchen while she cooked. These childhood memories still evoked in Edward a sense of well-being, washed in magic.

Slowly he stands up. He leans a hand on the windowsill and looks out. Close to the right of the house is the old wooden gate, swinging in the rain’s wind. How many years since he saw his mother opening that gate to the garden, turning around in her straw hat and closing it carefully so the clasp would catch? How many years had he been searching to find what no one had ever found before, some rare genus of cacti? How many months since he’d returned, worn out from lack of success, only to find his mother dead, too far away now for that long overdue bow of gratitude? How much longer could he afford not to sell her house?

He considers getting dressed but sits back down by the window again. Noon comes and goes. He stares straight ahead. As the light angles sideways, the emptiness in him deepens. He watches the sun glistening off his mother’s silver teapot, the only silver she ever owned. He had wanted to buy her more, a sugar bowl and milk pitcher, but instead, for the last ten years, he’d rarely answered her letters. She never complained, only sent loving thoughts and always a tin of her shortbread biscuits he dearly loved. He was far too anxious and fearful to be so generous.

As the sun drops closer to the horizon, Edward closes his eyes. He doesn’t want to admit that he is sad. But more than that, he now realizes, he is afraid of this sadness. Afraid that should he succumb, he might never rise again.

How could he be afraid of sadness? He was Edward Stanwich who handled poisonous plants as if they were geraniums. He was the man that crossed the baked earth at night without a lamp or map, simply because there might one lone Cactaceae. Why, for the last four months, he’d sat at this very window working on his treatise; diligently and well into the night. He’d cooked his own meals and done his own laundry. He’d taken long walks at night alone, with dogs barking and sometimes the howl of a coyote. He’d learned not to pay attention to fear, treating fear like an irritating bug and quickly scratched away. But now this.

He looks down past his slippers to the shaggy brown carpet. There he can see his mother’s indentations from her garden clogs, tracking into the kitchen, up the stairs, to her bedroom. All the years alone in this house, taking care of the daily chores, fastidious in her simplicity.

He stands up. He looks into the kitchen as if to find assistance in the white tile, the full refrigerator. Finding none, he goes back to the window and sits back down. He has only the awful present with no hope for completion, his findings no nearer the end then they’d been two years ago.

Again, he pulls himself out of the chair. This time he starts up the stairs. All he wants now is to go back to bed. It is something.

Human dignity, dreams, reality, the present moment, the past, the future – all collide and Edward finally gives up. He doubts the validity of everything he has ever done.

Let it be said, Edward is a fine man. He never lied or cheated or betrayed. And in his small way, he left the world a better place.

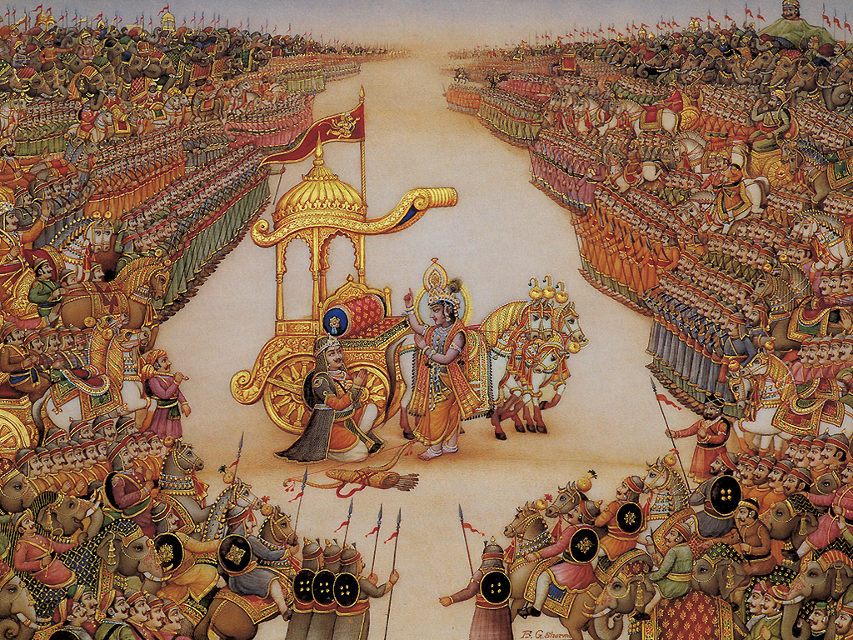

Let it also be said, Edward did not at this crossroad blame anyone or anything but himself. He knew he was afraid and filled with sorrow and self doubt. He also knew he couldn’t continue living unless he faced them. He’d hoped reading The Bhagavad-Gita would help. Hadn’t Krishna told Arjuna that it was better to battle one’s self than to kill another? But Edward felt incapable of any fight. Even his mother had tried often to stir him to action but it was no use. He was the way he was and he had to accept that. He had no choice.

Edward was once on a train destined for Ankara, the capital of Turkey, with appointments planned and people waiting. He is staring absently out the window. A few trees, an occasional village, goats and an endless brown landscape blur past.

The train makes an unexpected stop. There is no station, only a small, concrete slab in the middle of a flat dusty plain. A man wearing a blue cap and the traditional Turkish pantaloons has waved down the train. Edward, bound for Ankara, strains forward in his seat, pressing his face against the glass, watching. Somehow he is being pressed to consume this scene. Something important is about to happen and he must be watching closely to catch on.

He watches the stranger out the window, gesturing wildly, obviously upset. The conductor steps out of the train. Edward, head pressed against the window, witnesses a heated conversation. The stranger bends down on one knee in a position of pleading. The conductor keeps shaking his head no, no, and tries to lift the stranger to his feet. The man continues to plead, wringing his blue cap. Finally the conductor looks at his watch and goes back into the train. Edward feels he should really do something but what? Stop the train? He couldn’t possibly do that.

After a few more tense moments, Edward feels the train lurch and pull away, with the stranger, still kneeling, still wringing the hat in his hands. Edward strains at the window as long as he can until the stranger is lost to the accelerating landscape out the window. Edward feels disturbed by this scene. What would his mother have done? He can’t decide what made him sad and on the verge of tears. Quickly he riffles through his briefcase and pulls out a magazine, anything for distraction. He finds an article about beetles that live off morning glory leaves. When a predator appears, the beetle changes its skeletal structure into that of a ladybug, those awful tasting insects to any palate, and the predator flies or crawls away. He is absorbed and takes a few notes. Arriving in Ankara, he is only six minutes behind schedule and reminded of the incident with the stranger. He feels uneasy. He might have helped in some way but did not. His mother would have helped, now he knows she would. That fact brings back the sadness but he has an appointment and realizes that not getting off the train means he isn’t late. At the meeting, his editor gives him an extension of six more months to complete his book. Relieved, Edward dines at an expensive restaurant nearby to celebrate with raki and baklava.

Back at the hotel, before falling asleep, he decides, definitively, to sell his mother’s house. He will finally rent that flat in London. Still, he cannot fall asleep, so he resorts to spinning a fantasy, this time about finding a rare blue flower high in the Alps. It was a dangerous trek. The tiny flower will be named after him. There will be an honorary dinner, replete with dignitaries. These flights of fancy will usually put him right out, ready for his eight hours of unconsciousness.

***

If Edward were a different man, which he isn’t, but if he was, this different Edward could have taken this same train bound for Ankara. As before, it would come to an unexpected stop. Looking out the window, this other Edward would have seen that same man begging to the conductor on bended knee. Except this time, in this alternate reality, Edward, this time without fear, steps off the train to see if he can be of assistance.

He learns that the stranger’s wife is very ill. The man is asking the conductor for help. The conductor promises he will call a doctor from the train but may or may not be able to get one. That’s all he can do, now he must be off; he is on a very tight schedule, ‘down to the minute’, and hopes his wife will be all right, perhaps it is very little and will pass.

Edward listens and suddenly finds himself telling the conductor he’ll take care of everything. He watches the conductor get back on the train, the train lurches and pulls away, picking up speed. The sound of the engine grows fainter until all is quiet. He looks around. Edward finds himself in the middle of nowhere with not a building in sight.

The story resolves rapidly. The wife only ate a little noxious weed and by the time the two men get to the family house, she has vomited it away. Edward is very much interested in what the weed looked like so the peasant woman walks him to a ravine and points. There, a single plant grows, pushing up out of the cracked earth, beside a skinny pool of brackish water. He kneels down and touches a leaf. It is pointed-oval, toothed and lobed, no more than two inches, on a stem some 20 inches high. And there are the berries, pure white, three-eights of an inch in diameter. She had eaten some, she says, only two.

None of the pieces fit. Central Turkey and Actaea rubra? But these aren’t its usual red berries but white. This is not a lower forest but a plain. Still, it once could have been. There are a few scraggy trees in the distance. He questions the woman and she says she collects weeds for food, always has, and came upon this plant she had never seen before. She always eats a bit before giving any to the family. This one she would certainly never touch again. She spits at the culprit and turns away. Edward carefully takes his pocket knife and digs up the plant, securing enough soil around the roots until he can pot it properly in Ankara. He gives the stranger money, which turns out to be more than the man earns in one year. He has a family of six.

Edward gets to Ankara the next day on the next train. He missed yesterday’s appointment by 24 hours. Doesn’t matter; he has other things to do. He goes to his hotel room and examines the plant. He verifies the plant is of the Ranunculaceae family, its berries extremely poisonous. Back in London, he compares his findings to other native baneberries. This one’s slightly different, the leaves and stem smaller. He will have to wait until it flowers. After blooming months later, the flowers are not the usual white but red, like the fire-red of salvia. The discovery is astonishing in Glasgow, leading him to be admitted to the Royal Horticultural Society in London and affording him the post of Chief Botanist for the Kew Botanical Gardens. He is only 45, the youngest ever to hold that post.

But Edward never got off the train. And he never does sell his mother’s house.

Author’s Statement on Beauty

How can we condemn nature to anything but beautiful? An osprey blanketing a salmon is a swing of precision, the lion nabbing a wildebeest a flagrant tango, an abandoned factory covered in purple thistle and heavy blackberries a feast. Everywhere is wonder and wonder is inspiring and inspiration exciting and excitement wished for and all wishes carry beauty. There is beauty in a sigh, a kiss, a tear, keening, hope, death. The brain is a miracle of profound beauty. All is perception so I strive to filter my reality through the clear lens of beauty.

Diane Parker is a freelance writer for a number of New England publications, and writes about artists and their work for West Branch Gallery in Stowe, VT, Vermont Art Guide, Kolaj Magazine, Art New England, and Mountain View Publishers, also serving as Gallery Director for White River Gallery in South Royalton, Vermont. She has recently completed a novel, Absolute Uncertainty, and is currently working on a short story collection.